Fiona Shaw likes shaking things up. In 1995, she polarized London critics when she turned “Richard II”—the first part of William Shakespeare’s Henriad tetralogy—on its head, by portraying the 14th century British monarch herself!

She may have overstepped the bounds of taste, however, in the searing but thematically cluttered one-woman play on Broadway, “The Testament of Mary,” Colm Toibin’s Tony-nominated revisionist drama, which imagines the Blessed Virgin Mary discussing her anguish and lacerating rage during her exile in Ephesus—where the Gospel of John is said to have been written—some years after the crucifixion of her beloved son.

Throng of protesters

Four days before we were scheduled to watch the controversial show, as we were on our way to a performance of “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” on 48th St., we were taken aback by the throng of protesters who peacefully gathered in front of the Walter Kerr Theatre just a block away.

As she told the New York Times’ Patrick Healy, Shaw was aware of the play’s “potentially sacrilegious” themes: “It’s not a fundamentalist tract challenging the basis of Judeo-Christian religion,” she explains. “Colm loves Mary, but his Mary is not the aloof, blue-veiled icon that you are offered in statuary. She’s a mother whose son is rather difficult (to understand)… The audience has to decide if Mary is a reliable witness to her own memory. She remembers things differently from how we’ve read them.”

In the show, the “recollections” Shaw refers to are nothing short of discombobulating, not so much because of how Jesus’ mother sees his disciples as “a group of misfits…who cannot even look me in the eye,” but because of the play’s disconcertingly contrarian tone.

After all, we’ve always considered Mary’s acquiescence as a symbol, not merely of divine providence, but also of fierce bravery. Besides, which Catholic wouldn’t get “shaken up” seeing the venerated Mary puffing cigarettes and stripping down to her bare essentials to take a dip in the pool?! Yes, we know our metaphors, but that’s taking creative freedom a little too far.

More previews

The play hasn’t exactly endeared itself to theatergoers, either: “Testament” had more previews (27) than actual performances (16)—and closed on May 5, long before its intended June 16 wrap-up.

Toibin said he did not want the show to be marketed to Catholics as “the most shocking thing you will ever see.” He explained: “I wanted the play to be a theatrical experience, rather than a culture war over religion.”

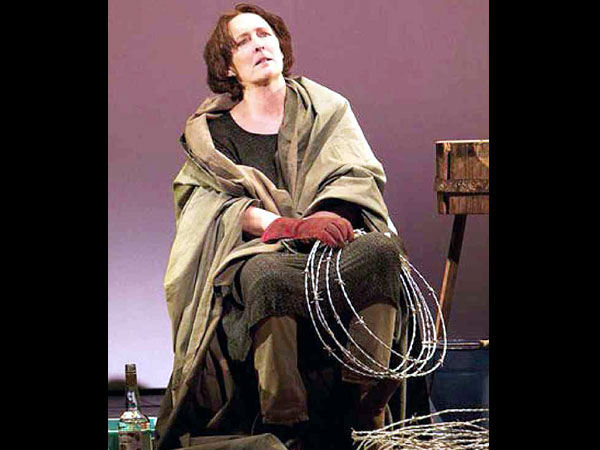

“Mary’s” ticket buyers were forewarned that they wouldn’t be seated if they arrived late. But, the production’s stern approach to tardiness was nothing compared to its befuddling staging: Before the show began, theatergoers had a field day taking pictures when they were invited to go onstage to take a look at Tom Pye’s minimalist set design—a folding table and some chairs, coils of barbed wire, a ladder, a vulture on a bird pole, and a transparent glass cube with Mary (Shaw) inside it, muttering incomprehensible lines around a sea of votive candles. Director Deborah Warner broke the fourth wall even before the play began!

From her disturbing first line, about the apostles who are in the process of writing the Gospels that would eventually constitute Church orthodoxy and hagiography (“They appear more often now, both of them—and, on every visit, they seem more impatient with me and the world.”) to the devastating last (“It isn’t worth it”), we empathize with her loss. —But, as she talks about her version of The Greatest Story Ever Told, Mary is stripped of her reassuring essence as the succor for our woes, etc.

Musings

As played by the acclaimed actress, Mary is haunted by her inability to save her son, bitterly recalling how she tried in vain to warn him of the danger to his life during the Wedding at Cana. The play’s ruminative musings on grief are eloquent (“His death belongs to me, not the world!”)—but, because it attempts to say a lot, it doesn’t end up saying much.

The 54-year-old thespian is a transfixing presence—she drips with irony and sarcasm as she rants about loss and guilt—especially after Mary allegedly left the scene of the crucifixion to save her own life.

But, even as she comes to grips with her character’s grief, Shaw lacks the necessary subtlety needed to neutralize—and humanize—Mary’s anger.

A truly insightful portrayal cannot merely rely on the temporary impact of its histrionic and thematic excesses!